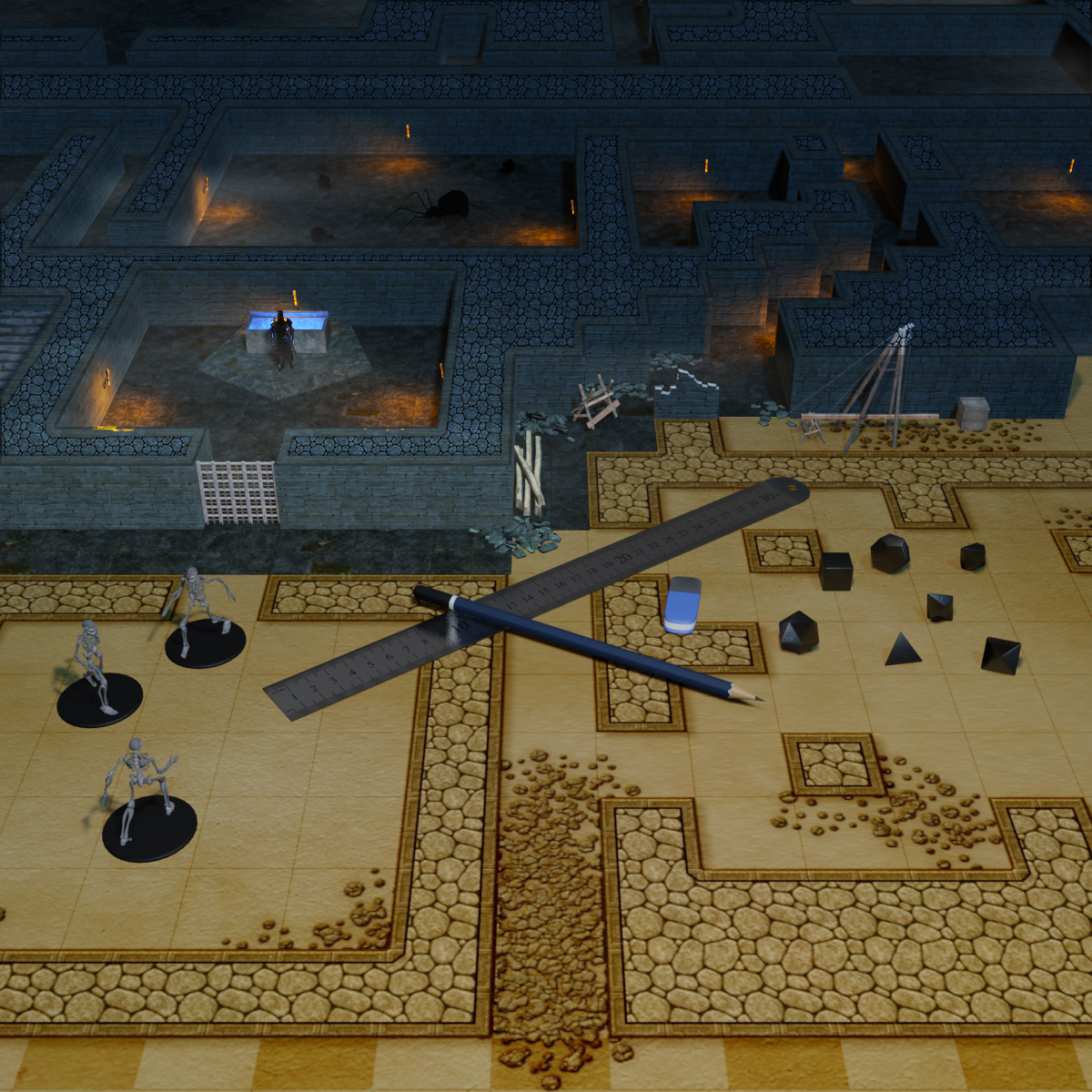

As game masters, we make a lot of dungeons (and by dungeon, I mean any sequence of rooms and corridors that a party is meant to explore). It can become all too easy to fall into the rut of putting in a few rooms and corridors and then dropping in some nasty traps and enemies and calling it a day. This generally leads to lackluster dungeons that the party clears quickly and then forgets even before they reach the exit. Sometimes this works and is what the campaign needs—a quick hack-and-slash dungeon run that the players don’t have to think about too much. However, dungeons that play a part in the ongoing narrative deserve a lot more attention so that the dungeon itself helps to tell the story and drives the party forward or in a new direction. Even for simple dungeon runs, understanding the story behind the dungeon can give it layers that make it feel more authentic in your players’ imaginations.

Understanding the story behind your dungeon can make it feel more authentic.

To make dungeons more interesting, we need to look at the story behind the dungeon and why the dungeon is even there in the first place. We don’t need to write a lengthy history for the dungeon, but it can help answer several key questions: Who built the dungeon? Why did they build it, and how? Who lives there now? What changes have been made? These questions help create a bit of history for the dungeon and support the overall design to give the dungeon a cohesive feel that sets it firmly into the campaign world and draws the players in. Additionally, answering these questions upfront makes it easier to come up with answers if the party begins to ask questions about the history of a dungeon and why a particular feature is what it is.

Who Built the Dungeon and Why?

Understanding who the original builders are and why they built the dungeon is crucial in determining the dungeon’s layout. An old and abandoned dwarven fortress may be constructed with large open chambers and broad linear passages. In contrast, goblin warrens are more likely to be a twisting maze of small natural caverns and tunnels. Suppose the dungeon is built for defense, such as a fortress or hideaway. In that case, the entrance is likely to be narrow or twisting with several choke points for defending against an attacking force and living spaces set as far to the interior as possible. On the other hand, a dungeon meant for containment, such as a crypt or prison, is likely to have larger staging areas near the entrance with smaller cells or crypts deeper inside.

Few individuals build simply for the sake of building. A dungeon is usually constructed for a specific purpose, and the layout of the dungeon should reflect that. When you build a dungeon to be part of particular plot points, such as facing a specific enemy or finding a particular item or location, it is probable that you already have an idea of who built the dungeon. For example, the party may hunt a tribe of kobolds and track them back to their tribal warrens, a twisting maze of dirt tunnels, and hollowed-out earthen dens. In this way, the dungeon reflects those who live there and tells the story that the kobolds are a bit more animalistic.

The current occupants of a dungeon may not be the original builders.

Many creatures would prefer to take up residence in an existing space rather than build something themselves, so it may be that the current occupants are not the original builders. This adds a layer of complexity and interest to the dungeon that the players may not expect or may lead to further adventures. Perhaps the party tracks the kobolds back to a narrow broken tunnel that leads into an ancient crypt that the kobolds have been using as a den. Crawling through the tunnel and into the crypt, the players are suddenly presented with something they did not expect, and that will immediately set them on their toes. Further, it leads to questions about who built the crypts and what else the party may find inside.

There are endless possibilities for who built the dungeon and why. The decisions you make here will help to shape the dungeon and inform further decisions as you go. You could decide that dwarves built the crypt to honor a hero of some forgotten battle. The crypt starts with a long straight hallway carved in deep relief with images telling the story of the dwarven hero’s life. Deeper into the crypt, solemn stone statues carved with such skill as to appear almost alive provide an eternal honor guard. Perhaps a cunning secret mechanism guards the entrance to the hero’s final resting place. This gives the party something interesting to explore while dealing with the kobolds that may lead to an unexpected treasure (perhaps the dwarven hero’s magical axe) or a new adventure (such as discovering who the hero was and tracking down their ancestors).

Changing the dungeon’s purpose or the original builders is a great way to add variety.

Alternatively, we could decide that the crypt was built by an unknown dragon cult to entomb an ancient dragon’s remains. The crypt may start with rooms dedicated to offerings left for the dragon’s spirit in the afterlife. These could be actual treasures or perhaps animal offerings, now little more than rooms of ancient brittle bones and dry desiccated hides—the grinning skull of a large horned steer sitting atop the pile. Tapestries depicting dragons and the cult’s practices or symbology may adorn the walls, while deeper inside a vast cavern houses the ancient dragon’s coiled skeleton. The kobolds may gather around the skeleton and worship it as a deity (or perhaps it is a dracolich). Changing who the original builders were, or the dungeon’s purpose is a great way to create variety to your dungeons and encounters, even if the current enemies are ultimately the same.

How was the Dungeon Built?

Once you understand who built the dungeon and the purpose it was made for, it can be helpful to know how it was built. The dwarven crypt may be created with the expert masonry of the dwarves, with large stone blocks fitted so perfectly not even a hair could fit through the seams and amazingly life-like carvings adorning the walls. Alternatively, the crypt may be built without the expected dwarven skill, maybe because they were in a hurry or something prevented them from exerting their expertise. This can add further layers into the dungeon’s story and mystery if the players choose to explore the idiosyncrasies. The dragon’s tomb may have been chiseled out of the solid rock by workers that were, in turn, sacrificed to the dead dragon, their bones mingling with the others with a hidden secret message chiseled into a shadowed corner. Perhaps the cult’s priests used magic to create the crypt, with perfectly flat seamless walls of quartz giving the feel of ice (suggesting maybe the dragon was a white dragon).

Answering these questions of who, why, and how not only make the history of the dungeon more interesting but can lead to ideas for the layout and decor that turn a simple set of rooms into a unique location. A location to be explored, investigated, and remembered.

Who Lives There Now?

The dungeon’s original builders define the space, as it was built for their purpose, but that doesn’t mean they are still using the dungeon. As in the kobold warren example, the original builders may also be the current residents, in which case the rooms are likely being used for their original purpose. Sleeping dens will be full of bedding or nesting materials, eating areas will contain foodstuffs and wastes, and a nursery will likely contain eggs and tenders. However, suppose the original owners have abandoned the dungeon for whatever reason. In that case, someone else is likely to move in and make it their own, changing features as necessary to suit their needs.

Someone is likely to move in and make an empty dungeon their own, changing features as necessary.

Again, if you’re building a dungeon as part of a specific plot point, you probably know who currently lives there and why. The party is likely hunting the inhabitants (such as the kobolds) or looking for something guarded by the inhabitants. Alternatively, the plot point may be the original builders of the dungeon, and the current occupants are there as an obstacle. In that case, you may already know who built the dungeon, but not the current inhabitants, if any.

In either case, deciding who or what currently occupies a dungeon will change the dungeon to some extent. If a bear were to take residence in an abandoned fort, it would likely turn one of the rooms into its den, filling it with bedding and the remains of its meals. A dragon taking over a castle is likely to take the biggest room as its lair or destroy walls to make a large enough room, all while gathering anything of value that it can reach in the castle and moving those treasures into its lair. Dwarves may take a natural cavern and carve and build it into the central hub of an underground stronghold.

Any creature taking over an existing space will modify the area according to their needs and the extent of their ability. An animal may only be able to move or destroy furniture or gather nesting material, while a skilled individual may be able to change the underlying structure. It is important to ask not just who lives in the dungeon now, but what their needs are and how they’ve changed the dungeon to meet those needs.

It is important to know who lives in the dungeon, what their needs are, and how they use the dungeon.

In the case of our kobolds, which are a small tribal society, you may decide that they need a central gathering place to eat and socialize as well as individual or family group sleeping dens. The shaman of the tribe needs his own space to work his magic, and there may be some sort of temple or shrine where the tribe makes offerings. The kobolds also need a nursery where they keep and tend their eggs. These are the basic needs, and knowing this, you can begin to explore how they may adjust the space to suit those needs.

If the kobolds live in the dwarven crypt, they may turn any smaller side chambers into family group sleeping dens and nests. The main hall may be lined with ramshackle lean-tos and hide tents housing the juveniles and individuals of the tribe. The bas-relief carvings will likely be defaced in some way, broken or painted with primitive drawings, and certainly covered in a thick layer of dirt. Garbage such as broken weapons, pieces of broken furniture, soiled cloth, and cast off food waste likely litter the long hall.

The kobolds may turn the sizeable central chamber where the dwarven statues stand guard into a meeting place for the tribe, with a large fire pit in the center for meals and socializing. Here the soot from the fire blackens the ceiling around a crudely chiseled hole that acts as a chimney. The statues might be defaced, perhaps even toppled, with ropes, crude banners, and filthy cloth draped around them. One wall of the chamber has been broken open, the earth behind hollowed out and turned into a small nursery where clutches of eggs are stored and tended. Finally, the shaman, who has figured out the interior crypt mechanism, uses that as his special magic place.

Personal touches make a dungeon feel “lived in” and give a sense that the occupants belong there.

Changes like this make the dungeon feel “lived in” and give a sense that even though the crypt was not built by the kobolds, they still belong there. They’ve made the space theirs. If we just dropped the kobolds into the dwarven tomb and made no changes, it would feel as though the kobolds were there only to hide briefly or had just discovered the crypt.

It is important to note that it’s not required to have just one current denizen in the dungeon. If the space is large enough, perhaps a beholder has taken up residence in the deeper levels while undead roam the upper levels. In this case, it is essential to understand if and how these denizens interact with one another. If they are combative towards one another, the dungeon’s respective areas are likely to be fortified against one another, with a sort of no-man ’s-land where the territories meet. Conversely, the different denizens may have an amicable or symbiotic relationship, in which they share space and territory via mutual understanding or assistance. A tribe of goblins may feed a rust monster, keeping it as a guard dog and metallic garbage disposal.

A Note on Traps

Traps are a particular problem for game masters attempting to make dungeons that make sense. Most individuals are unlikely to put a dangerous trap anywhere that they may accidentally trigger it. It is easier to place traps in a dungeon that was never meant to be entered (such as a sealed crypt) to deter looting or keep others from taking up residence. When dungeon creators add traps to an occupied dungeon, they tend to be set out of the way (either in secondary or back entrance) or to protect a specific location or item from everyone, including the residents (such as a vault or secret chamber). If the residents need to get past the traps, they will need a way to bypass the traps safely. Always keep in mind the residents of the dungeon when placing traps. How do they avoid the trap? Why would they set a trap there? Is the trap something they could actually build? These are vitally important questions you need to ask before adding a trap.

Putting Everything Together

Knowing who built the dungeon, why it was built, and who lives there now adds depth to an otherwise uninteresting setting. The decisions made here lead to creating truly unique spaces that lend themselves to writing interesting room descriptions. It can often be difficult to know how to fill a particular room so it’s not just an empty space. Thinking about the original builders or the current owners can spark ideas for unique features, enemies, treasures, or mysteries that you may not have considered. I generally find that it’s much easier to add a lot of details to a dungeon using this method and that when players come up with an unexpected question, it’s much simpler to come up with an answer that makes sense.

Your players gain a sense of accomplishment when they figure out a part of the dungeon’s story from the details.

Your players won’t always notice all the details you add, and they may not care about the story of your dungeon, but it is far more likely that they will if your dungeon actually has a story. And when the players do notice, those details often lead to further adventures and truly memorable sessions. The other benefit of thinking about dungeons this way is that your players can make intuitive leaps from the details they have been given and gain a sense of accomplishment when they figure out a part of the dungeon’s story on their own. That’s when you know that you’ve created something special.

Hopefully, this method helps you develop something new or enables you to add a bit of depth to your dungeons. If this is something you already do, we’d love to hear about your most unique ideas and the dungeons that your players still talk about years later. As a bonus, you can download this simple Dungeon Designer Worksheet to help you plan out your next dungeon.

Happy adventuring!

Want to continue the conversation? Join Our Discord

Commenting has been disabled for this post.