I love puzzles, both as a Player and Game Master, and I’m not alone in this. A well-crafted puzzle is a thing of beauty that can create unique role-playing moments and help to immerse your players into the game. Although many people enjoy solving puzzles (look at the success of escape rooms), few people enjoy getting frustrated over puzzles they can’t solve. And that is the problem with puzzles in tabletop games; all too often, they are nothing but exercises in frustration.

Player Ability vs. Character Knowledge

The first hurdle to overcome when crafting your puzzle is differentiating between the player’s ability to solve puzzles and their character’s intelligence and knowledge. We can often overlook a character with low intelligence whose player is skilled at solving problems. This dichotomy doesn’t hurt the fun of the game, nor does it contribute to player frustration. When the situation is reversed, and the character has high intelligence, but the player is not good at solving puzzles, players often become frustrated. This frustration stems from the fact that the character should be able to solve the puzzle, even when the player can’t. In this situation, you need to let the character solve the problem in case the player gets stumped. Your players’ enjoyment is more important than your well-crafted puzzle.

Your players’ enjoyment is more important than your well-crafted puzzle.

The other aspect of player versus character knowledge that causes issues is when a puzzle is based on in-game lore that the character knows, but the player may not. For example, if a gatekeeper requires the name of the third Queen of a particular dynasty to let the players pass, you need to ensure that that information is available to the players. You could give the players information with a skill check or conspicuously plant the info before encountering the gatekeeper, such as on a statue, in a book, or mentioned by an NPC. The thing to keep in mind is that the farther in time the information is discovered from when it is needed, the more likely the information will not be recalled. A good rule of thumb is to make sure the required information can be found within the same dungeon it will be needed.

Just How Difficult is It?

One of the more challenging aspects of building a puzzle is controlling the level of difficulty. When we create puzzles, we tend to do so in reverse, planning a solution and then developing the puzzle around that solution. Crafting a puzzle in this way is often necessary (to ensure solvability). Still, it does mean that we, as creators, have no fundamental concept of how difficult the puzzle is to solve. Since the solution is forefront in our minds, we often create puzzles that are far more difficult to solve than we expect.

As game masters, we only get one shot to get it right.

Have a friend try to solve the puzzle before you put it in your game.

One of the advantages that escape rooms have is that they frequently have a team that builds puzzles together, and they can adjust the difficulty if players are having trouble solving it. As game masters, we only get one shot to get it right. When building a puzzle, you should try to get others to look at and solve it before you put it in your game. Doing this can help you dial in the difficulty level or correct any issues with the puzzle (such as alternative solutions you may not have thought of).

What Do I See?

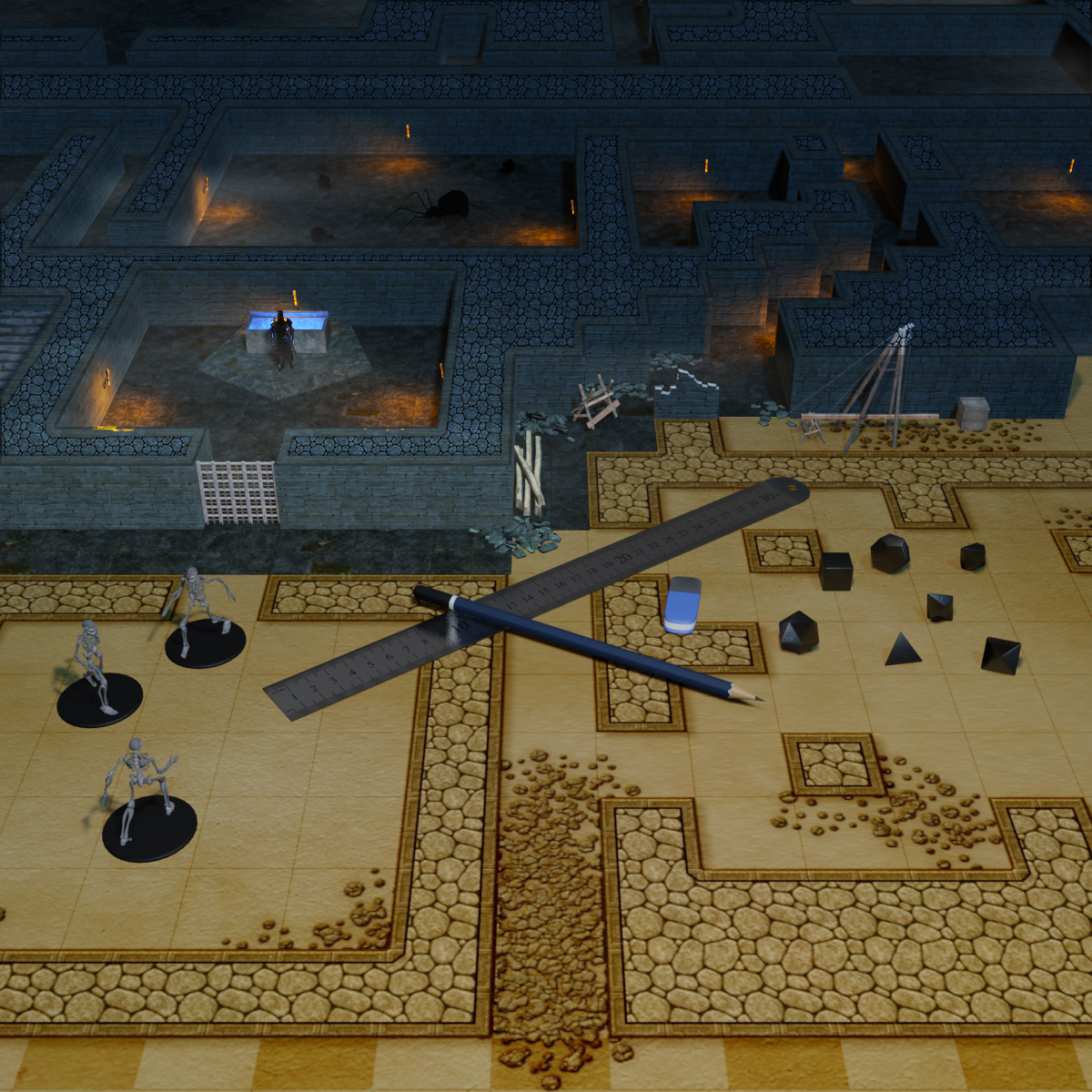

One of the reasons escape rooms work so well is that the puzzles are tangible. The players can see and examine the puzzle or manipulate it in multiple ways to better understand the problem. When we describe a puzzle to our players, especially a complex puzzle, the clarity of our description and our players’ mental image is often all they have to come up with the solution. The problem is that no two people’s imagination is the same. Additionally, the longer a puzzle takes to solve, the more the players’ mental image will degrade, increasing the difficulty and leading to frustration. Whenever possible, you should endeavor to have a handout for your puzzle. Something your players can hold, examine, and review if they get stumped. This handout can be a piece of paper with a riddle on it, an image of the puzzle itself, or an interactive representation of it. Anything that your players can see reduces their need to rely on memory and imagination and helps reduce the frustration associated with a puzzle.

Overthinking

The other problem with puzzles isn’t one that you can solve in your preparation. Sometimes people overthink the problem, no matter how simple the solution may be. One of the most well-known examples is the entrance to the Mines of Moria in the Fellowship of the Ring, Book II, by J.R.R. Tolkien. The Doors of Durin are sealed such that the seams are invisible, with an inscription carved into the door. As translated by Gandalf, the inscription reads, “The Doors of Durin, Lord of Moria. Speak, friend, and enter. I, Narvi, made them. Celebrimbor of Hollin drew these signs.” Though he eventually does come up with the correct password to open the door (“friend,” in elvish), he spends a lot of time stumped due to overthinking the problem.

It’s not as complicated as you’re making it.

You will find that the simpler the solution to your puzzle, the more likely your players will overthink the problem. You can let your players run with it in the hopes that they eventually take a step back and reconsider the puzzle, or you can let them know they’re overthinking it. If your players spend a long time trying to make an intricate solution work, a simple “It’s not as complicated as you’re making it” may get them back on track and keep the game moving.

The Danger of Time Limits

One of the things that escape rooms implement that does not work as well in a tabletop setting is time limits. In an escape room, if you have an hour to solve the room, it doesn’t matter whether you complete the challenge or not; after an hour, the experience is done. When we add time limits to puzzles in a tabletop game (e.g., a descending ceiling or room filling with water), it does create tension that we might be looking to add, but it also creates a potential endpoint for the adventure. If the puzzle is one that is required to continue forward and has but one chance to get it right, should the party fail to solve it, your adventure is done. There’s now no way forward, and the party must abandon the adventure (provided they survived whatever the challenge was). If you want to have a puzzle with a time limit or a limit to the number of tries, it should always be for something not critical to completing the adventure (such as a side room or extra treasure). Unless, of course, you want the adventure to have a chance of potential failure due to the puzzle (though I wouldn’t recommend it).

Another Way Forward

Ultimately, no matter how perfect our puzzles are, players will eventually get stuck. If you have no way forward other than solving the puzzle, the rest of your adventure will be wasted if your players can’t get there. If your players are stumped, your game will come to a halt, and your players will get frustrated (and possibly decide to quit the current adventure). When this happens, we often resort to letting the players get by with a few dice rolls or a “deus ex machina” solution to save the adventure.

If you have no way forward, the rest of your adventure will be wasted.

The following is an example from one of my games that suffered most of the issues listed here. I planned the encounter poorly; it was more difficult than I imagined, relied on my description and player imagination, and they completely overthought the situation. In the end, I ended up using a deus ex machina “accident” because I hadn’t planned another solution.

The party was at the entrance to a royal tomb; in this first chamber, there was a stone throne with a seated skeleton. The skeleton wore a silver crown and held a silver scepter in its lap. Next to the throne was a staircase leading down to a large iron door set below floor level. An inscription above the door read, “Tomb of the Line of Drass, Only Those with the Blood Shall Pass.”

My players spent over an hour trying everything they could think of to open the door. They manipulated the scepter and crown in every possible way, they each shed blood on the door in hopes that they had some royal blood, and they examined every inch of the throne and chamber. Nothing was the “correct” solution, and they just got more and more frustrated. I had thought the way past this door was obvious (because I knew the answer). Since the door was meant to seal the royal tombs, either a living or dead royal was needed to open the door. Fortunately, there was one sitting on the throne. However, my players never thought to bring the skeleton to the door because I used the word “blood.”

When my players were just about to give up, I allowed the skull to fall to the floor and roll down the stairs the next time the party jostled the skeleton. The door opened, it was cheesy, and the game continued—definitely a learning moment.

Want to continue the conversation? Join Our Discord

Commenting has been disabled for this post.